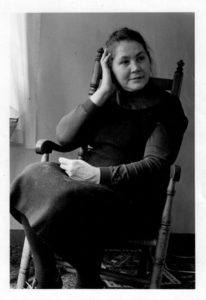

This series matches footstools from my mother Paula Trepanier Harris’s collection with rocks I have collected around the world. The aesthetic pleasure I take in gazing at individual stones grows out of looking at furniture with her growing up, going to antique shops with her in search of distinctive pieces. “Does it have the look?,” she would ask, as she deliberated buying a chair or stool.

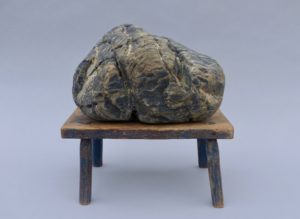

Each composition in this series marks the culmination of many hours spent trying out different stones on the stools, playing with them until a pair would pop with some form of ‘the look,’ at least to my eye. While the match between the two components is often a matter of texture, size, form and color, the relation between elements does not remain constant. For instance, the beach sandstone below rests like a cushion on the ca. 1720 Queen Anne’s stool.

Produced during the pandemic in the period after Paula’s passing, the project explores mortality, mourning, and material forms of memory. These works also reference and riff on viewing stones, individual rocks mounted on carved bases (such as Chinese scholars’ rocks).

Produced during the pandemic in the period after Paula’s passing, the project explores mortality, mourning, and material forms of memory. These works also reference and riff on viewing stones, individual rocks mounted on carved bases (such as Chinese scholars’ rocks).

Stones and stools are humble, often overlooked objects; beneath our feet or seat, they are often beneath our notice. Scrutinized closely, though, they expose material archives of wear and tear over human and geologic timescales. The textures inscribed in paint and patina record traces of minute events and infinitesimal encounters.

Stones and stools are humble, often overlooked objects; beneath our feet or seat, they are often beneath our notice. Scrutinized closely, though, they expose material archives of wear and tear over human and geologic timescales. The textures inscribed in paint and patina record traces of minute events and infinitesimal encounters.

These temporal repositories are tantalizing in that simultaneously reveal and conceal the past, providing tangible but taciturn testimonies of untraceable histories. In addition, I have only limited records of the provenance of the stools and petrology of the stones: a few notes my mother left about some of the stools (e.g., “ca. 1800, original paint”) and scattered insights gleaned from geologists into the likely origins of certain stones. Yet I also discovered that digging for facts about the objects in fact moved me further away from them, interfering with the immediate intimacy I felt with them.

These temporal repositories are tantalizing in that simultaneously reveal and conceal the past, providing tangible but taciturn testimonies of untraceable histories. In addition, I have only limited records of the provenance of the stools and petrology of the stones: a few notes my mother left about some of the stools (e.g., “ca. 1800, original paint”) and scattered insights gleaned from geologists into the likely origins of certain stones. Yet I also discovered that digging for facts about the objects in fact moved me further away from them, interfering with the immediate intimacy I felt with them.

In working on this project, I found mourning to be haunted by virtual ghosts, the regrets of words not spoken or opportunities not taken. One begins imagining retroactive versions of things as they might have been, people as one would have wished them to be, relationships as they may have been otherwise. I learned that mourning is about letting go, including letting go of retrospective revisioning and owning the irreducibility of one’s fallibility.

In working on this project, I found mourning to be haunted by virtual ghosts, the regrets of words not spoken or opportunities not taken. One begins imagining retroactive versions of things as they might have been, people as one would have wished them to be, relationships as they may have been otherwise. I learned that mourning is about letting go, including letting go of retrospective revisioning and owning the irreducibility of one’s fallibility.

Collecting can be a lifetime practice. The creation of a collection produces pockets of order amid life’s randomness and temporarily staves off the world’s chaos of contingencies. Since these constructions represent intersections of two collections, they constitute even more radical reversals of time’s entropic erosion and scattering of matter. They therefore lodge protests against the very loss of time that their components register; they are also gestures made fully cognizant that what a human joins together, time will inevitably put asunder.

Collecting can be a lifetime practice. The creation of a collection produces pockets of order amid life’s randomness and temporarily staves off the world’s chaos of contingencies. Since these constructions represent intersections of two collections, they constitute even more radical reversals of time’s entropic erosion and scattering of matter. They therefore lodge protests against the very loss of time that their components register; they are also gestures made fully cognizant that what a human joins together, time will inevitably put asunder.